“It was tough giving the order to execute Che”

Fifty years after revolutionary’s death, ex-CIA agent recalls informing Guevara he was to be shot

Miami

Former Cuban CIA agent, Félix Rodríguez, 76, who played a key role in the CIA mission that captured Che Guevara in 1967 in Bolivia, welcomes us into his home in Miami where he is surrounded by memorabilia from the Cold War era – pistols, knives, grenades, photos with US presidents and spies who are no longer with us.

Félix Rodríguez, at his house in Miami. GIORGIO VIERA

A Vietnam War veteran, also known for his involvement in The Bay of Pigs and his anti-communist activities in Nicaragua, Rodríguez is to be the subject of a documentary by Spanish producer Scenic Rights. There will be a particular focus on his involvement in Che Guevara’s execution.

On this subject, Rodríguez insists that the CIA wanted the revolutionary alive, but the Bolivian government gave the order to shoot him. “I tried to save him, but to no avail, “ says Rodríguez, who did, however, consider Ernesto Guevara de la Serna “a murderer.”

On a small table at his side, Rodríguez has an old Spanish-made Star pistol. “Watch out when you pick it up,” says the man who posed with Che in a photo taken shortly before his execution. “It’s loaded. I always keep something to hand just in case.”

I tried to save him, but to no availFORMER CUBAN CIA AGENT, FÉLIX RODRÍGUEZ

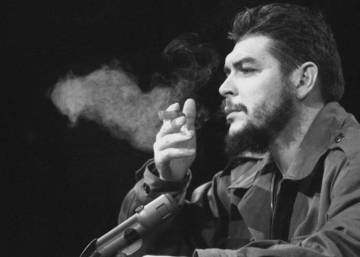

This last photo of Che alive was, he explains, taken by the helicopter pilot Jaime Niño de Guzmán in the village of La Higuera where Che was being held. Asked who wanted the photo taken and why, Rodríguez goes back to 1967 in his mind and says: “Let me tell you the story.”

“We were informed that Che Guevara had been captured on the morning of Sunday, October 8. A group of young soldiers had been trained in the local languages of Quechua, Aymara and Guaraní so they could be sent ahead of the battalion in civilian clothes to gather intelligence. And these guys came back at 7pm that Saturday to tell Captain Gary Prado that a peasant had shown them an area called the Quebrada del Yuro where the guerillas were hiding out – this peasant had a vegetable patch near there and had seen them.

“Armed with that information, Gary Prado surrounded the Quebrada del Yuro that night. And on Sunday morning, October 8, he began his advance and the shooting began. Che got a bullet in his left leg between his knee and his ankle but nothing life threatening. Most of the guerillas and some Bolivian soldiers died in the shoot-out and Che Guevara was taken prisoner, despite the efforts of Simeón Cuba Sarabia, a short Bolivian revolutionary otherwise known as Willy, who tried to help him escape. Cornered, he said, ‘Don’t shoot! I’m Che Guevara and I’m worth more alive than dead.’

“So they took him to the school in La Higuera and put him in one of the rooms with the bodies of two Cubans behind him. Then they wired me coded information that said: ‘Papá tired’, meaning that the guerilla leader had been captured alive. But we didn’t know if ‘Papá’ was Che Guevara or Inti Peredo who was the Bolivian guerilla leader. So we flew to the operative area and confirmed that ‘Papá cansado’ was Che Guevara, whom they called ‘the foreigner’.

“That night we celebrated at the Vallegrande Hotel by candlelight because there was no electricity and I brought out a couple of bottles of Scotch that I had bought for an event such as this. That was Sunday night, the day he was captured.

“The next day at 7am, Monday, October 9, we took a small helicopter piloted by Niño de Guzmán to the school where Che was being held and where the battalion officers were waiting for us, among them Lieutenant Colonel Selich who had all Che’s documentation. Che used a leather bag, like a woman’s bag, to carry a thick German diary in which he wrote in Spanish. He also carried photos of his family, medicines for his asthma and several small books with messages in numerical code that were impossible to decipher. And he had small black ringed notebooks containing typewritten papers signed by ‘Ariel’, which were messages from Cuba. He, of course, could send nothing back to Cuba because Cuba had deliberately given him a broken transmitter – he had actually been sent there by the Cubans so he would be killed. Che was pro-China and Cuba depended on the Soviets. And the Soviets had no interest in Che Guevara winning in Bolivia. They abandoned him there, so he would be finished off.

“So we went into the school and there was Che, his hands and feet tied, lying on the floor below a small window with the two bodies behind him. The only person who spoke was Colonel Centeno Anaya. He asked questions, but Che just looked at him and didn’t say a word. Until, finally, the Colonel said, ‘Listen, you’re a foreigner, you have invaded my country. The least you can do is have the manners to answer me.’ But he didn’t speak.

Then I asked the colonel if he could give me Che’s documents so I could photograph them for my government and he gave Lieutenant Colonel Selich orders to hand them over. They gave me the leather bag and I went off to process the papers. I photographed the diary and then I went back to talk to Che. I went in and out constantly until 1pm. During this time, the phone rang and one of the soldiers came to me and said, ‘My captain, a call.’ I went to the phone and they gave me an order from the Bolivian military high command ‘500-600’. It was a very simple code: 500 meant Che Guevara; 600 meant dead; 700 meant alive.

“I asked them to repeat and they confirmed: 500-600.

Sometimes I would be speaking to him but I couldn’t concentrate on what he was telling me. I had never seen him in person beforeFORMER CUBAN CIA AGENT, FÉLIX RODRÍGUEZ

“I took Centeno Anaya aside and said, ‘Colonel, instructions have arrived from your government to kill the prisoner. My government wants us to save his life and we have helicopters and planes to take him to Panama to be interrogated.’ But he replied, ‘Look, Félix, these are orders from the president and military high command.’ He looked at his watch and said, ‘You’ve got until 2pm to interrogate him. And at 2pm, you can execute him however you see fit because we know the damage he has done to your country. But at two in the afternoon, I want you to bring me Che Guevara’s body.’ And I replied: ‘My Colonel, I have done my best to influence the decision, but unless there is a counter command, I give my word as a man that I will bring you Che Guevara’s body.’”

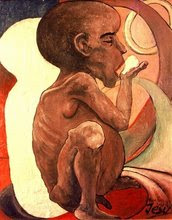

“Later, while I was talking to Che, the pilot, Niño de Guzmán, came with a Pentax camera from the chief of intelligence and said, ‘Major Saucedo wants a photo of the prisoner’. I looked at Che and said: ‘Comandante, would you mind?’ And he said, ‘No, I don’t mind.’ He walked with difficulty because of the bullet in his left leg – but we left the school and stopped to take the photo. I gave my own camera to the pilot and I said to Che, ‘Comandante, look at the birdie.’ He started to laugh because it’s what we say to children in Cuba: ‘Look at the birdie’.

“I even think he was still laughing when the photo was taken, but, obviously, he changed his expression to the one you see now. I was in Special Forces uniform but without any badges. I was just 26 then. He was 39. He looked like a beggar. His clothes were worn and filthy. He had no boots, just pieces of leather tied to his feet. His hair was bedraggled. To be honest, sometimes I would be speaking to him but I couldn’t concentrate on what he was telling me. I had never seen him in person before, but I remembered photos of him from a visit to Moscow with the Russians and when he visited Mao Zedong in Beijing – photos of an arrogant man in those damned coats. And to see him now looking like a beggar. It made me feel sorry for him.”

Question. What did you see as Che’s biggest defect, and as his greatest virtue?

Answer. I don’t think he had any virtues. What I can say is that the guy was true to his ideals, which were clearly misguided and disastrous. People who had trained with him spoke about his perseverance. He would be tired and finished, but he tried to keep going. He wouldn’t give up. But, he was also a murderer who enjoyed killing people and who was full of hatred for his enemies. He was someone who sent thousands of Cubans to their death.

Q. Was his capture the crowning achievement of your career?

A. It was one of my first achievements and it’s the one I’m most known for.

Q. Is there any mission you were involved in that pains you to remember?

A. Possibly the hardest was when I had to pass on the command from the Bolivian Government to kill Che. Although I also thought of the disaster he had caused in my country.

Q. Did they give the command in front of Guevara?

A. No, they told me and then I went into the room where he was and stopped in front of him and I said, ‘Comandante, I’m sorry. It’s a command from above.’ And he understood exactly what I meant.

Q. What did he say?

It’s better this way. I should never have let myself be taken aliveCHE GUEVARA

A. He said, ‘It’s better this way. I should never have let myself be taken alive.’ Then he took out his pipe and said, ‘I want to give this pipe to a Bolivian soldier who was good to me’. So I took the pipe and asked him, ‘What about your family?’ And he replied with an edge of sarcasm: ‘Well, if you can, tell Fidel that he’ll soon see a successful revolution in America’. I understood that what he was saying was, ‘You abandoned me, but this is going to happen anyway.’ Then he changed his expression and said, ‘If you can, tell my wife to marry again and try to be happy.’ Those were his last words. He took my hand and we embraced, then he stepped back and stopped dead, thinking it was me who would shoot him.

Q. What did you do with the pipe?

A. That was one of the things I regret. I took out the tobacco – now, I have some of the tobacco from his last smoke stored in one of the guns I use. Then Sergeant Mario Terán came to me and said, ‘Captain, I want the pipe. I killed him so I deserve it!’ Not wanting to have to carry out his dying wishes after all he had done to my country, I gave the pipe to the sergeant. ‘Here, something to remember your deed by,’ I said. And he took the pipe, lowered his head and left.

Q. What aspect of that episode had the biggest impact on you?

A. Seeing a man on his knees

Q. What did you feel when you talked to him?

A. To be honest, at that time I wasn’t aware of what was happening, of the enormity of the mission. As far as I was concerned, it was just another operation. Che Guevara didn’t seem to me to be a big deal – he wasn’t the figure he was made out to be after Cuba.

Q. Were you surprised by anything he said?

A. Each time I asked questions of tactical interest, he replied: ‘You know I’m not going to answer that.’ There was also a moment when we started to speak about the Cuban economy and he put all the blame on the American embargo. And I said, ‘Comandante, you were at the head of the National Bank of Cuba and you weren’t even an economist.’ And he said, ‘Do you know how I came to be president of the bank? One day I understood Fidel was calling for a loyal communist, so I raised my hand. But he was actually asking for a loyal economist.’

Q. Did you witness his execution?

A. No. I wasn’t interested in seeing it. I went elsewhere and I sat on a bench 100 meters away and took notes. I heard a brief blast and made a note: 1.15pm. The exact moment he was killed.

English version by Heather Galloway.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario